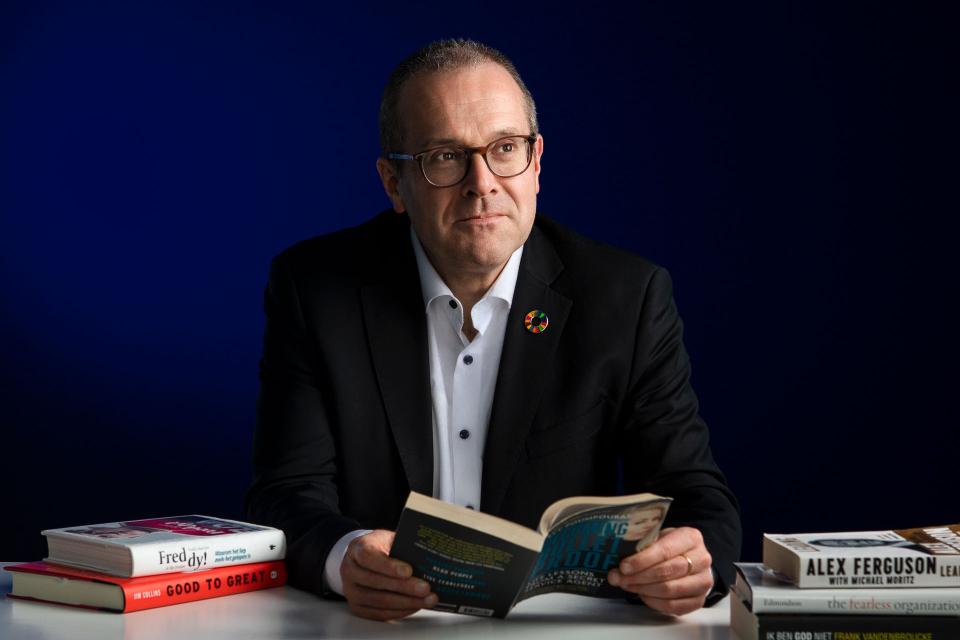

Hans Kluge's World of Reading

Schopenhauer famously said that reading is thinking with someone else’s head. But what is it that we hope to find in the other person’s head? Peace and quiet, distraction, knowledge? Welcome to the World of Reading, a series of interviews in which we talk about the role of reading, beauty, and language. In this instalment: Hans Kluge, Director WHO Europe.

Interview by Matthias M.R. Declercq

Translated by Sandy Logan

-> naar de Nederlandstalige versie van dit artikel

‘I’ve always kept this book’, says Hans Kluge. He is seated at a large, wooden desk in Copenhagen and holds up Oejarak to the camera, a children’s book by Karel Verleyen. In the background, the blue logo of the World Health Organization (WHO, a United Nations agency) is visible. There is also a flag in his office. Hans Kluge is in the centre of the screen, after which the camera zooms in and it looks as if he is about to give a speech. Something that he has done on many occasions in his career. But Dr Kluge brushes off the formality and instead tells me about a young boy named Oejarak. ‘He is a Greenlandic Inuit boy who was very sick as a child. He has a leg injury which is why everyone in the village calls him ‘gimpy’. I really enjoyed reading this book as a young boy, in Roeselare (West Flanders) where I grew up. It was quite a special experience, to travel to Groenland in my mind, thanks to this book, a place that I found very difficult to imagine. ‘The back cover of the book tells us that Mr Kristensen, Oejarak’s Danish teacher, doesn’t always understand him. The story of an Eskimo boy in search of his roots, in a society that hesitates between the old, traditional lifestyle and western civilisation. I am leaving on an expedition to Groenland in a few months’, says Dr Kluge, ‘together with the Director-General of the Danish Public Health Ministry. We have come full circle: the relatively independent people of Greenland have requested external medical assistance. And I will finally get to meet the Oejaraks myself.’

Bulletproof

Doctor Hans Kluge is the regional director of the WHO in Europe, a gigantic organisation that helps shape and coordinate the health and well-being policy of 53 European countries. Without wanting to compare their political ideas, you could say that Dr Kluge is the Charles Michel of European health. In recent years, he lived life in the fast lane: his team was in charge of guiding our continent through the pandemic. They also had to deal with monkey pox, polio, and the crumbling mental resilience of large groups of people after successive lockdowns and the related social isolation. But the director read more than just papers and reports during this period. ‘Sometimes I read thrillers to escape all the bad news, usually on holiday, in our house in the Dordogne, where we have no internet’, he says. ‘But at the end of the day, I didn’t read that much fiction. My reading world mainly consists of non-fiction with a marked preference for books about management and coaching. I also read lots of biographies: you can learn a lot from the lives of others.’

‘I love to read on the plane. I spend a lot of time travelling to different countries and in the air people leave me alone. I don’t have to do anything and can really take the time to read.’

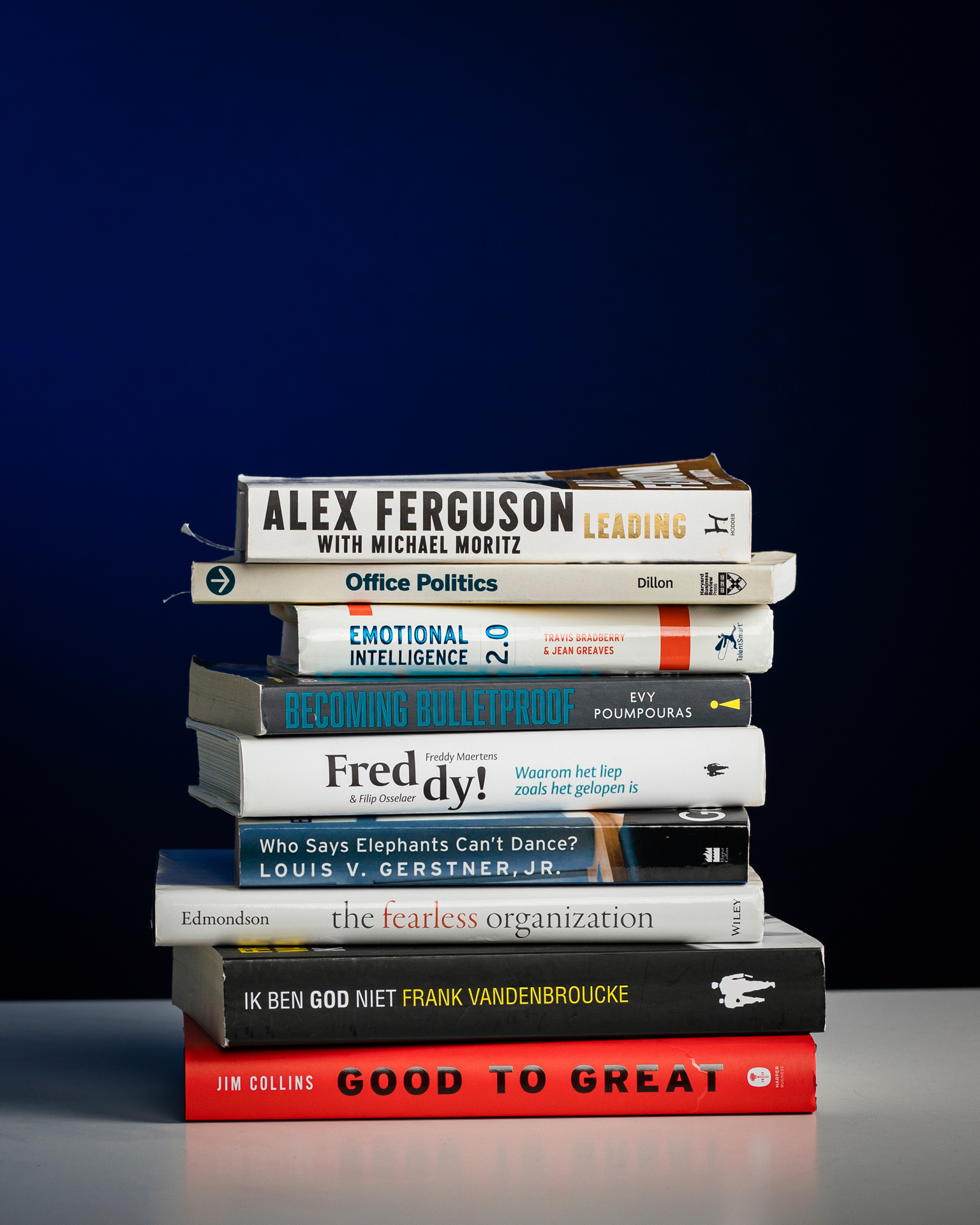

There are several books on his desk: Leading, the biography of Alex Ferguson, the former manager of Manchester United, the football club; the biographies of former cyclists Frank Vandenbroucke (Ik ben god niet) and Freddy Maertens (Freddy! Waarom het liep zoals het gelopen is) – because Freddy is from Lombardsijde just like Dr Kluge’s dad –; and a slew of management books, including Who Says Elephants Can’t Dance (by Louis V. Gerstner, Jr. about the technology corporation IBM) and Good To Great (by Jim Collins, about why some companies are successful and others aren’t) and Becoming Bullet Proof (by Evy Poumpouras, essential life lessons from a secret agent). ‘My wife gave me that one’, says Dr Kluge. ‘She is a Russian philologist. We met in Siberia, where I was conducting research into tuberculosis in the former Russian gulags. This is such a fascinating book. It explains how you can arm yourself against specific dynamics in a large organisation. How you can stay mentally, morally and physically resilient without having to give up your values. This is the kind of book that you can apply both to your professional and private life. Management books keep your mind sharp, which is important. People tend to like things, to resign themselves to things very easily. But you need to keep on evolving. The WHO is 70 years old and needs to be agile, and less bureaucratic.’

30 minutes of study

‘When one of my teachers retired, I asked him what was his motto in life. ‘Never stop reading’, he said. When you stop reading, you stop writing and you become less creative. My dad had and has a different motto: ’30 minutes of study every day’. He was the head surgeon in the hospital in Roeselare and he always reminds me that you can always learn more, that you always need to be one step ahead. I have followed his advice and I have tried to pass it on to my daughters. Because those 30 minutes of study, which can just consist of reading a book, boost your self-confidence. That is what reading has given me: confidence. To read more is to know more. It also helps you to anticipate on situations. When a European Health minister calls me, I want to be able to add something to the conversation.’

“That is what reading has given me: confidence. To read more is to know more.”

Myanmar

To be honest: of all the interviewees so far in this series, Dr Hans Kluge is best prepared. Prior to the interview, the regional director of the WHO in Europe rang his parents and sister. ‘My parents were quite surprised’, he says. ‘Hans, why are you asking us about books from your childhood?’, they said. (laughs). My father told me on Skype that he read a lot of medical books in the past, that my mother used to read a lot, and that they read their children – my sister and I – books like Annie M.G. Schmidt’s Pluk van de Petteflet. They instilled a reading culture in me. But it helps to have a wife who is a philologist. When we lived in Myanmar (ed: where Kluge also worked for the WHO), I also read Pluk van de Petteflet to our daughters. Admittedly, my wife did more than I did – the family mainly speaks Dutch – because I spent a lot of time travelling. I mainly remember Wendy Cooling’s De grote verhalenparade. A book with children’s stories that take two, five or ten minutes to read. I would start with a two-minute story, but the girls always managed to convince me to read more. Reading to children is so important. Everyone stands to benefit. In Opvoeden tot geluk (van Jacqueline Boerefijn & Ad Bergsma, about teens and puberty), a book that I read in Myanmar, the author clearly demonstrates that the time that you spend reading to your child is almost directly proportional to your child’s happiness. Because this develops a close relationship between the parent and child.’

“Reading to children is so important. Everyone stands to benefit. It develops a close relationship between the parent and child.”

Mental health

Saying that reading has a major, positive impact on the mental health of children (and adults) is easy. But when the European director of the WHO does this, this carries more weight, it is more meaningful. ‘For a long time, Iceland had major problems such as alcoholism, substance abuse and crime. They developed special programmes to tackle these issues from several angles. One of the measures stipulates that parents are legally obliged to read to their children every day for five to ten minutes. This is not the only reason why Iceland overcame its problems, but it definitely plays a part in this. A lot of research also indicates that art, in any form, including literature, also has a positive influence on your self-confidence and self-awareness. Reading is a form of mindfulness, a way of relaxing, it gives you time to reflect. It keeps your brain healthy and active, which is important in the prevention of dementia. My grandmother took English lessons late in life and although my father is 88 years old, he still sees patients.

Reading, including fiction, teaches you things. This is an important stimulus, but these days it is sometimes lost in the multitude of stimuli that we encounter in life. I asked my daughter in the run-up to this interview: doesn’t the audiovisual world have too much of an impact on you? My daughter laughed: ‘Dad, you are so old-fashioned, you can’t stop it!’ Norwegian research has shown that teenagers increasingly are reporting mental health issues, including anxiety and trouble sleeping. They find it very difficult to live up to the ideal image that is touted online. This is detrimental to their ideas on sexuality, for example. Am I worried about the audiovisual dominance? I take it very seriously. There is more to come. Society – parents, schools … – needs to take its responsibility. Reading can help. It is a never-ending source of knowledge and relaxation.’

Container

A reading world often involves a bookcase, but not always. You can spend your whole life going to the library. But the physical embodiment of your reading world consists of more than some shelves and a bunch of cracked spines. It is also a home. Hans Kluge’s home will always be in West Flanders. That is where he learned to read. Where he went to school. Where his world was shaped. He has kept many of the books that he read at the time, such as Oejarak. Even when he lived in Moscow. He moved his books from Belgium to Russia, and later to Myanmar. And so did his wife. She took her Russian library, with books by Chekhov and Dostoevsky, with her to Asia. ‘At the time there was no internet in Myanmar’, says Dr Kluge. ‘The government had banned it. To avoid feeling alienated, to feel at home there, I took a bunch of Flemish films with me. And even though I was exhausted after a long day of work and I felt generally drained, it always felt good to see the books on the shelves. And to open one and read a few pages. Giving me an opportunity to unwind. Phew.’

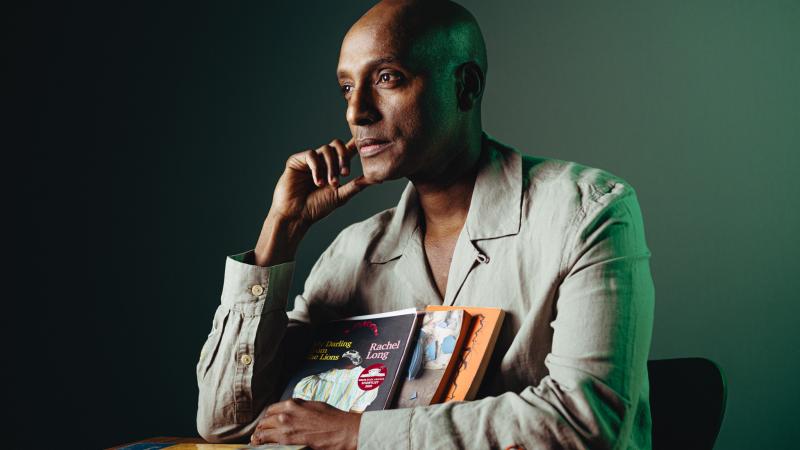

Worlds of reading

Discover more inspirational interviews with readers.